Urban green spaces are considered one of the most appropriate and accessible ways to mitigate the effects of rising temperatures in urban environments. As the global climate warms, cities worldwide face more frequent and extreme heat waves, putting their citizens at risk. Many cities are employing strategies for reducing the impact of urban heat islands, which are generated when natural land cover is replaced with surfaces that absorb and retain heat, such as pavements and buildings. This raises the temperature by several degrees compared to the surroundings. Cities have their micro-climate, influenced by this phenomenon combined with a series of often overlooked factors. For a climate strategy to be efficient, all factors need to be taken into consideration.

Heat risk levels are also strongly correlated with the social structure of the city. Neighborhoods with less affluent and historically marginalized sectors have less access to green spaces, putting them at greater risk. Through planning regulations and land zoning, the impact on the disadvantaged citizens can be lessened, improving their health, well-being, and standards of living. Scientists like Winifred Curran and Trina Hamilton are pointing out that improving the vegetation can lead to increased property value and can lead to the displacement of long-term residents. They suggest a strategy called “just green enough”, creating strategic interventions to support local communities.

Green Corridors and Climatological planning

In 1938, the forward-thinking German city of Stuttgart decided to appoint a meteorological graduate to study the climate conditions and their relationship to urban development. The city is located in a valley basin with low wind speeds. It is also heavily industrialized, relying on automobile manufacturing infrastructure, and densely populated. The combined conditions resulted in poor air quality and high levels of pollution. This early study is considered by many as the beginning of “Urban climatology.” Just one year later, at the outbreak of the Second World War, the urban meteorologist was appointed to organize civil air defense measures, which included using artificial fog to hide from air raid squadrons, a somewhat effective action before radar technology. After releasing large amounts of artificial fog, it was discovered that the fog cloud dissipated more quickly than intended in certain areas. At the same time, it tended to linger for longer in other districts. The involuntary large-scale study considerably impacted urban planning, as it generated awareness about fresh air corridors and their influence on urban climate.

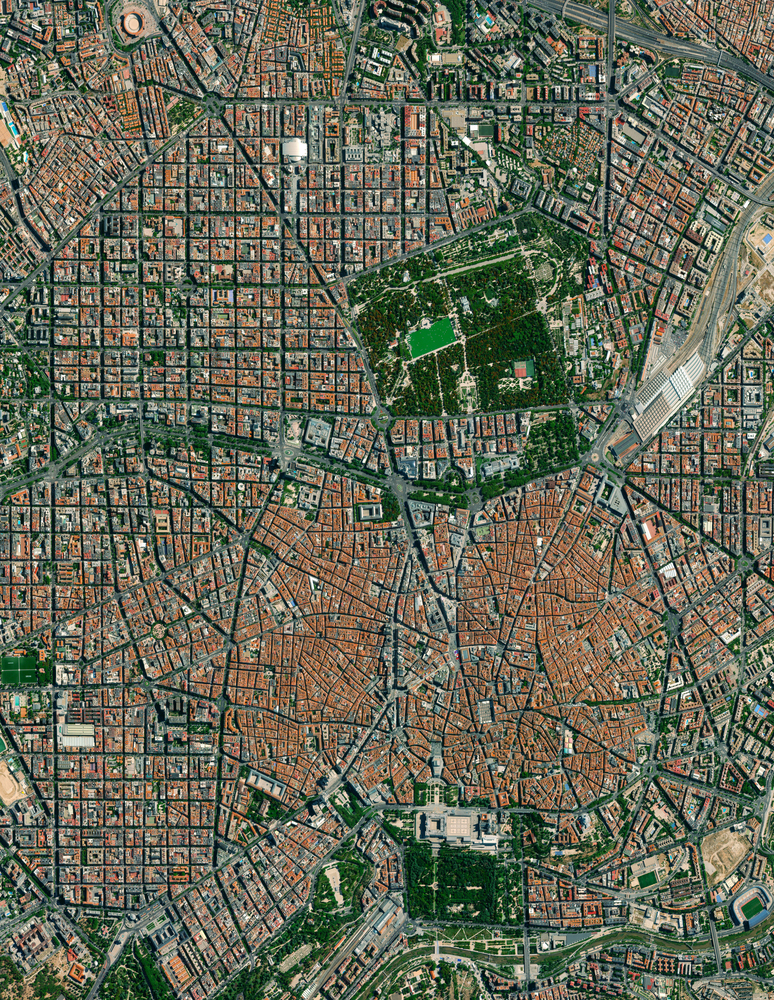

Through planning and regulations, Stuttgart encouraged open space development of the hillside parcels to allow air currents to sweep down the forested hills surrounding the city. Geographical features such as rivers, valleys, and other green spaces are protected as ventilation corridors in the urban plan, allowing prevailing winds to harness cooling services. In managing rising temperatures, the first challenge is understanding the topography, working with it, and protecting the location’s natural assets.

Regulating Micro-Climates

Green spaces are known to reduce the average land surface temperature, but their cooling effects have limitations. In most conditions, over 100 meters away, these effects can barely be perceived. Their surroundings’ topographical and geometric shapes can determine how far the cool air can penetrate, as heat sources and physical buildings often form barriers blocking airflow. Because of this, raising the amount of green coverage without considering their local conditions can only have limited efficiency in reducing urban warming. In dense urban areas with limited space availability, understanding these conditions is crucial to creating an effective strategy.

Large green spaces are preferable to create stable, cool islands, but not every city can implement them. Studies show that small clusters of green areas can also help distribute cool air and significantly lower urban heat. Distributing small green spaces around larger cool islands such as rivers or parks can also extend its benefic effects to a larger area. The type of vegetation also used matters. Plants take water from the ground and slowly evaporate it through their leaves, thus lowering the air temperature, a process called evapotranspiration. Trees are more efficient than shrubs and grasses because of their larger leaf surface and their ability to provide shade.

Tree-lined Streets

The street geometry affects the microclimate of a city in a complex way. Their width and orientation determine the surrounding buildings’ solar exposure. In hot and dry climates, narrow streets are recommended to ensure adequate shading and avoid overheating. On the other hand, narrow streets can limit air movement and disrupt natural ventilation channels, an aspect especially important in wet climates. In contrast, wider streets allow wind circulation but increase the amount of direct sunlight at both street level and surrounding buildings. Planting trees along the streets can efficiently offset some of the adverse effects of street geometry. A tree canopy covering at least 40 percent has been found to counteract the warming effect of the asphalt.

Green spaces in cities can fulfill a multitude of roles: they can become spaces for social interaction, recreation, and play; they can provide habitat for wildlife and increase the biodiversity of cities; vegetation can help in noise reduction and act as a pollution filter, in addition to helping rainwater management and temperature regulation. Associate Professor Wan-Yu Shih from the Department of Urban Planning and Disaster Management at Ming-Chuan University, Taiwan, warns, however, that all these roles might not be able to co-exist. Strategic planning is needed to define the most impactful functions green spaces can play in the efforts to adapt the urban environment to the social and environmental challenges they face.

Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά